For all its perceived advantages, like, for example, not having to commute and working when you want to, remote working also has its challenges. Loneliness is a primary risk and will have a very real impact for the thousands of UK workers who now suddenly find that remote working is going to have to be the ‘new normal’ for an unspecified amount of time due to the spread of the coronavirus.

At Thinking Focus, we have worked remotely for years, so it is so much our ‘normal’ that we would probably initially struggle to adjust to working in a central place of work and fit into a structure of regulated office time, physical meetings, commuting to and from work and working shoulder to shoulder with our colleagues. We’ve learned a few things over the years and would like to share some of that with you.

A real focus for your own well-being – let alone remaining effective when you have to work remotely – is making sure that you never feel isolated or alone. Here’s how to stay connected as a remote worker, including as an employee and as a person, during any time of uncertainty.

Set up regular remote meetings

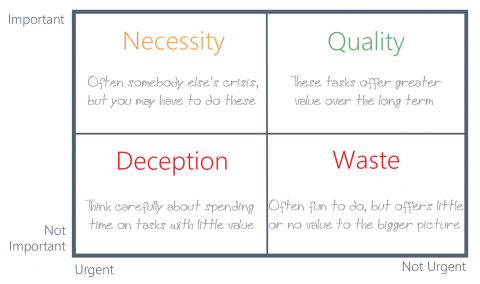

Getting regular, consistent feedback is an important part of productive remote working. If you’re the manager of a remote worker, or a remote worker yourself, consider implementing some of these strategies for staying in touch:

- A daily check-in: It’s always good to make sure that everyone’s on the same page and that everyone knows which daily tasks to prioritise.

A weekly team meeting: When you’re working remotely team, it is important to hear about what other people are working on—even if it’s outside of the scope of your focus. It helps to keep you connected. - Video is more personal than a conference call—and can help bond a team together, setting the groundwork for collaboration (even at a distance). After all, much of communication is non-verbal. faces need to be seen & expressions interpreted.

- Regular person-to-person meetings: Regular video calls with other remote teammates is important. Plan days to work together. You can use the time to share business updates, individual successes and failures, even social, non-work related chat for a time. The point is to feel more connected to each other.

Designate an in-office contact for remote workers

Now that you are practically away from your normal place of work, it can be easy to feel out of the loop—or worse, like your concerns or questions aren’t being addressed. One way to combat this issue is to designate an in-office contact. This person can be a manager, or they can be on the same level as the rest of the team. Part of their responsibility would be to make sure that team conference calls run smoothly by letting remote workers have equal air-time and making sure that issues are heard. In some cases, you’ll need a manager or an HR professional to help set up this designated role.

Find a remote working buddy

Friends and colleagues will be immensely important right now. People with a work buddy typically feel more engaged with their work than those without one. Try to find someone that you can regularly check-in with who can help keep you motivated when working alone. Don’t wait until you feel loneliness taking hold.

Use a remote working office platform

Communication is clearly the key to successful remote working. Find an effective office platform where team workflow can be monitored and important documents shared. This will provide a transparent way for everyone to monitor each other’s progress, as well as their own.

Communicate about more than your remote work

Keep in touch with your co-workers about more than just your daily tasks. If you can, try to stay up to date with people’s birthdays and what’s going on in their lives. Don’t be afraid to talk to other people about things that aren’t specifically about work – relationship building and maintenance is critical right now.

Set up a helpful remote work routine

Feeling more connected is not all to do with the office. Remember to keep connected to the rest of the world. Don’t get caught up in being or feeling isolated.

The workday should have room for enjoyment. Whether that means creating a light-hearted connection channel with friends online or simply giving a friend or family member a phone call when you complete a difficult task, don’t hesitate to take breaks and reward yourself for putting in the time and doing good work. Having fun is also part of the productive rhythm of a workday.

Stand up and walk around whilst on the phone. Remember to stop and have a meal – physically set the time aside. Build in time for exercise and fresh air.

Photo by Stefano Pollio on Unsplash