by Graham Field

One of the greatest challenges that leaders face in the workplace is how to motivate their employees. How best do we inspire and support them to increase their performance?

There are many theories around employee motivation, but in the this blog we’ll be giving practical suggestions that all leaders can put in place immediately.

To start with, we’d recommend that leaders assess how much they understand their team members’ motivations. This can be done simply by drawing up a table like this:

| Team Member: |

What Motivates Them? |

What Demotivates Them? |

| A:

B:

C:

D: |

|

|

The challenge is for leaders to see how many individuals in their team they could honestly complete this table for. Our guess is that many would find it a struggle! High quality leaders know these basics and use this knowledge to actively motivate their people, avoiding doing the things that they know cause demotivation.

Let’s now turn our attention to three sources of thought which we think are important in employee motivation, engagement and performance.

-

It makes sense for us to use this commonly-cited source as our starting point. Created by pollsters Gallup, it measures employee engagement and its impact on business outcomes by asking employees to complete a survey. The survey questions cover 12 areas of consideration, which we cannot directly quote because they are under copyright.

However, the questions look at areas such as expectations at work; rewards and recognition; opportunities and progression; relationships between colleagues; materials and resources; leadership and support; communication; belonging, purpose and mission; and quality of work.

Asking questions around these areas are really important and give us a great insight in to some of the motivating factors of all employees (ourselves included). But leaders then need to do something with the information they get from asking such questions.

In fact, they need to then answer some questions themselves! Examples of what they could think about are:

- What could I do to ensure that all my people clearly understand what is expected of them?

- How could I make praise & recognition a daily habit for my team?

- What could I do to ensure everyone is constantly involved with driving the business forward?

- What opportunities might I create for growth for my people?

And then, of course, they need to be proactive in committing to actions based on their answers to increase employee engagement and guarantee performance.

-

Ohio University Research

In 2000, Ohio State University carried out research into Human Motivational Factors (the things that drive our behaviour). Their research highlighted 16 different basic desires that affect behaviour. We think five of these have the biggest impact in the workplace, so let’s look at each in turn:

This is described in the research as “our desire to learn”. For us, this is an important factor in employee motivation. Leaders need to think about their people and the opportunities for learning that are available to them. From our work with organisations, we recognise that many people are given (or forced in to) ‘opportunities’ through training programmes. But, how focused is this development in terms of both what they really need to be a high performer and what they really want for their own development?

As a leader, ask yourself: How could you ensure that the desire to learn is (appropriately) fulfilled in your people?

This is highlighted as “our desire to make our own decisions” and, in our experience, it’s something that many employees may feel divorced from. Leaders need to consider what opportunities exist for their team members to make decisions. It’s not necessarily always about what they do (these will, after all, reflect your team or company goals), but certainly about how they can achieve them. Many managers will highlight what they need people to achieve, which does give focus. But they will also insist on the way in which things must be achieved, and this can stifle creativity, limit continuous improvement and ultimately demotivate. High quality leaders understand that the ‘What’ may need to be told, but the ‘How’ should be within the gift of the employee to decide.

As a leader, ask yourself: What freedom could you give your people to enable them to decide how to achieve your team goals?

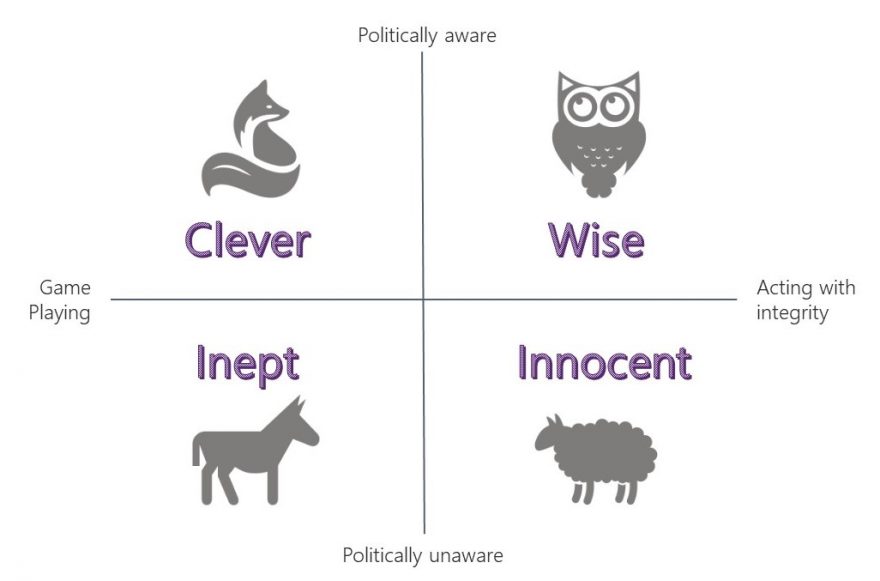

This is described as “our desire to behave in accordance with our code of conduct”. More simply put, it’s about ensuring that our values are met in whatever we do. Many people are demotivated by what they see as a lack of congruence between their personal values and how the company they work in is operating. One a leader’s roles is to understand the values of their people and help them to align these values with where their organisation is headed. As a leader, ask yourself: What could you do to ensure there is ‘values alignment’ for your people?

Quite simply, this is “our desire to influence people”. It’s one of the more curious Human Motivational Factors, but it’s something that can be seen every day in the workplace as people strive to gain the buy-in of others for mutual success.

As a leader, ask yourself: How can you use influencing techniques with your team? (this is a whole different blog altogether!)

Something that many of us desire is order – in other words, we crave the certainty and organisation that daily routine and habits give us. We all have things that we do in a certain order, and most of us strive to be much more organised and structured. The number of people we’ve helped with their time and personal management demonstrates how important order is to us. We’re big fans of giving supporting structures and certainties to people, as long as they work, bring about success and allow for individual involvement.

As a leader, ask yourself: What structures or order might your people need, and how could you ensure these are put in place to support your team?

-

Ron Clark, former ‘Outstanding Teacher of the Year’ at Disney’s American Teacher Awards

We believe strongly that inspiration can come from many areas, and the story of Ron Clark shows us that, no matter what your walk of life, when you’re looking to develop the motivation to perform, there are some simple things you can do.

Ron was a teacher in in a tough New York school when he won his award in 2000. He went on to become a New York Times bestselling author and a motivational speaker on the subject of inspiring educators.

We’ve picked out three of the areas he highlights when talking about motivation in the classroom, which we think continue to be very relevant in the workplace.

Setting stretching, yet achievable, targets works! People will generally perform to the level that’s expected of them. If we expect little of people, they will match our expectations. The flipside that we, as leaders, can embrace is expecting great things from our employees – and giving them the skills, tools and resources to enable them to meet our raised expectations.

As a leader, ask yourself: What expectations could you set that might challenge and stimulate your team?

It seems really easy – and really commonplace – for the negative stuff such as lack of achievements to be brought to the fore. But building in celebration and praise are essential tools in developing employee performance and maintaining motivation.

As a leader, ask yourself: What might you find today that you could praise and celebrate?

We recognise that there is value in having an interest in your people – and, as Ron suggests, this should be a genuine interest. At the simplest level, this is being interested in the response to questions; really wanting to know the answer to “How are you today?”.

As a leader, ask yourself: How could you develop a genuine interest in your team, and how could you show that you really are interested in your people?

As leaders, there is no magic wand we can wave to increase employee engagement and performance. However, one thing we can do is to invest quality time in understanding what makes our people tick. This forms the very basis of any aspect of managing people, and is the building blocks of high performing teams.

We recommend taking time to invest in your people and find out what really motivates them. After all, they really are the best asset your organisation has.