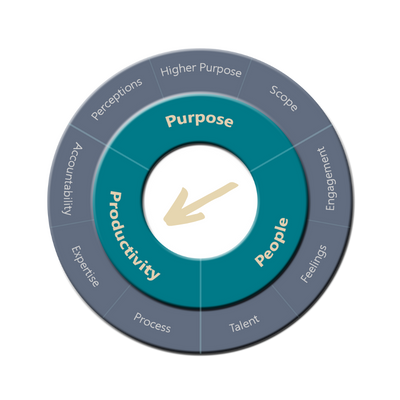

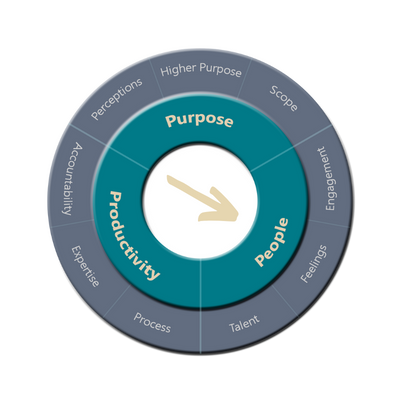

This article, the final instalment of the “Areas Every Leader Must Master For Success” miniseries, emphasises the pivotal role of productivity in achieving business success. Following discussions on purpose and people in the previous parts, this piece delves into the essential elements leaders must focus on to drive productivity: process, accountability, and expertise.

In today’s fast-paced and ever-changing business environment, leaders play a crucial role in balancing speed and precision, ensuring that processes are efficient and adaptable. Their efforts in effective process management can prevent inefficiencies and errors that often arise from hastily implemented workarounds. Leaders can enhance operational efficiency and drive sustainable progress by actively fostering a culture of continuous improvement and standardisation.

Accountability is another cornerstone of productivity. Clear roles and responsibilities within teams ensure that projects are completed on time and without costly oversights. The article highlights the importance of defined accountability in preventing project delays and missed opportunities, emphasising that shared accountability can lead to confusion and risk.

Lastly, the article underscores the critical role of expertise in leadership. Leaders must possess subject matter knowledge and know how to effectively empower their teams. By setting clear standards and fostering a culture of collaboration, leaders can harness their teams’ collective expertise to achieve shared goals.

The article concludes with critical questions to help leaders evaluate and enhance their approach to process management, accountability, and expertise. This practical checklist guides leaders committed to driving productivity and achieving excellence in their organisations. Leaders can position their teams for success in a competitive and dynamic business landscape through a focused approach to these areas.

This final part of the three-part miniseries “Areas Every Leader Must Master For Success” focuses on productivity, following on from purpose in part one and people in part two.

In business, productivity is crucial for success and hinges on three key factors: process, accountability and expertise. As leaders, we ensure efficient processes, clear ownership of tasks and the right expertise within our teams. We create a winning combination that drives our company’s triumph in the competitive landscape by fostering collaboration and effective governance. Prioritising these elements empowers our workforce to excel and secures our position at the forefront of the industry.

Let’s unpack each key area in more detail.

Process

Businesses operate at such a fast pace, determined to win in their chosen field. The volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) landscape means leaders have to seize opportunities. The leader’s challenge, however, is they may travel too quickly for their people, so project implementations and integrations are partially completed, leaving their teams to cope with workarounds. Workarounds are inefficient, prone to error and often create key-person dependencies in high-change environments. I worked on three mergers in quick succession. The next one started before the previous one was complete. It felt like we didn’t get the time to do any of them justice: good enough and compliant, but with apparent gaps.

Complex mergers rarely deliver against the original brief; yes, things change, and what you thought was under the hood is often very different when you open it up. All companies have foibles, quirks and workarounds of their own. Understanding this means the assumptions change the game’s rules, and you must adapt. We all face fast-moving change, so it’s crucial to reprioritise what you feel constantly is essential. It’s no wonder that McKinsey reports that 70% of change projects fail to achieve their intended outcome.

Leaders must strike a delicate balance between conformity and change, fostering a culture of efficiency and continuous improvement. They should champion standardisation to streamline operations while encouraging innovative approaches to drive ongoing progress.

Accountability

Imagine you’ve worked on a project for 18 months; it’s all coming together, and you’re almost ready to go live. You are at the project go/no-go meeting when someone asks, “Have we got local government permission to access the site?” The room is deathly silent; the murmurs signify that someone has screwed up.

What happens when accountabilities aren’t clear can be catastrophic.

What if this was a new product going to market at a specific time to steal a march on the competition?

Google’s research into what makes teams highly effective highlights (among others) three areas: dependability, structure, and clarity, which involves clear roles and responsibilities. When no single person has accountability, you leave your outcome to chance. It’s the same with shared accountability: “We’ll pick that up.” There’s wriggle room, which means massive risk with “I thought they had got it” comments.

The 18-month project I just mentioned was actual. It led to a three-month delay. New people who were trained and ready to go were temporarily relocated. There were costs not budgeted for, lost revenues and missed opportunities. However, this experience also presented a significant learning opportunity in accountability, demonstrating the positive outcomes that can arise from a culture of shared responsibility.

Leaders must find the delicate balance between effectively organising the group and not micromanaging. They should facilitate consensus on decision-making processes and hold team members accountable for their commitments. This culture of collective responsibility ensures efficient progress toward the higher purpose.

Expertise

The challenge for many leaders is that their leadership journey involves them ascending the ranks and being promoted for their technical prowess and subject matter expertise. As a leader, there are different expectations; you now have subject matter experts reporting to you. The tendency for new leaders especially is to overplay their knowledge to the detriment of their team.

I remember my early career as a new leader in a contact centre. My expertise was in people and processes, not technology. I had a steep learning curve. It was humbling to defer to subject matter experts, yet I still had to fight my tendency to dive in and “fix” stuff that was in my comfort zone.

Leadership is about combining subject matter expertise and leadership skills. Leaders should set standards and ensure proper governance, leveraging their expertise to bring diverse talents and viewpoints together and driving progress toward the shared objective.

Questions to Ask

This next section lays out a set of questions to help leaders ensure they have considered the key areas under productivity. They provide a checklist for leaders to define, check, and balance: how to strive for the right people doing the right things at the right time and in the right way.

Process

- How do we decide on the what and the how?

- How do process and structure work in this setting?

- How do we know our communication flow is fit for purpose?

- How do we iterate and continually improve?

- What is our process for challenge and testing?

- How do we track and adjust our key performance indicators (KPIs) and progress?

Accountability

- How could we optimise the way we organise?

- How do we provide clarity on who does what?

- How do we ensure decisions are consistent with our standards and align with our purpose?

- How do we hold each other to account?

- How should we govern the expertise in each function?

- What are our leadership standards?

- What is our tolerance for performance?

- How do we standardise expectations?

- How do we measure results?

- How could we drive continuous professional development?

Effective leadership goes beyond theories and styles; it focuses on action and practice in critical areas of purpose, people and productivity.

Within this entire series, leaders will find a comprehensive checklist that will enable them to steer their teams toward success and make a lasting impact. A strong sense of purpose, a thriving team culture and a commitment to productivity set the stage for outstanding leadership in today’s dynamic business landscape.

This article first appeared on Forbes.com on 26th September 2023

Ricky has been a regular contributor to the Forbes Councils since 2023, where he shares his perspectives on all things leadership, change, culture and productivity, all with Thinking Focus’ unique perspective on metacognition, or as we prefer to say, thinking about thinking.