Once upon a time running a business was all about having the right resources or equipment, yet for most 21st-century organisations it is the people that make all the difference.

In this podcast Ricky, Rob and Rich explore the leader’s responsibility to ensuring that they have the right people to deliver their vision. From attracting the right people in the first place to developing the skills and experience required to deliver tomorrow, leaders have to invest in their talent, because talent is the only thing we have to make our businesses unique.

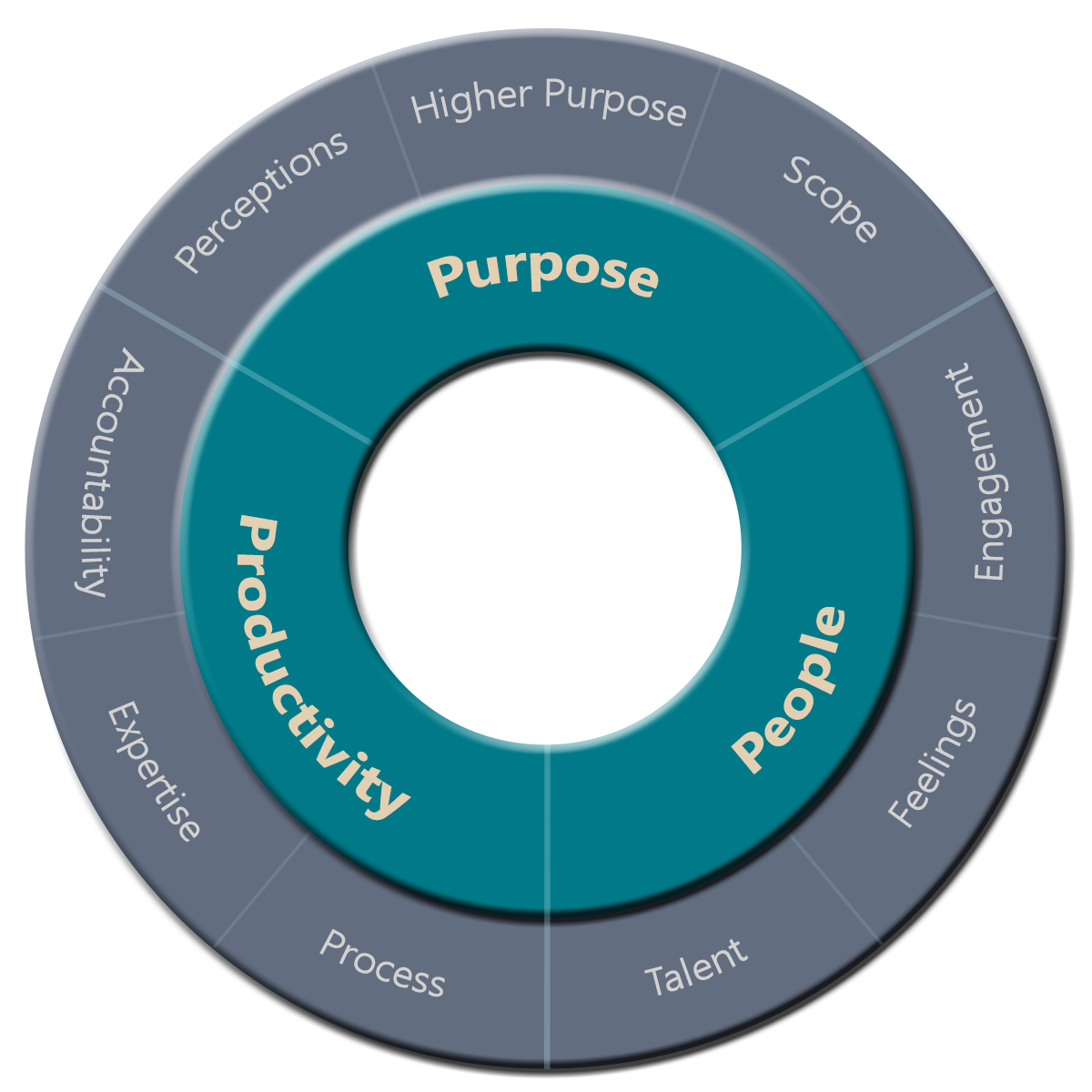

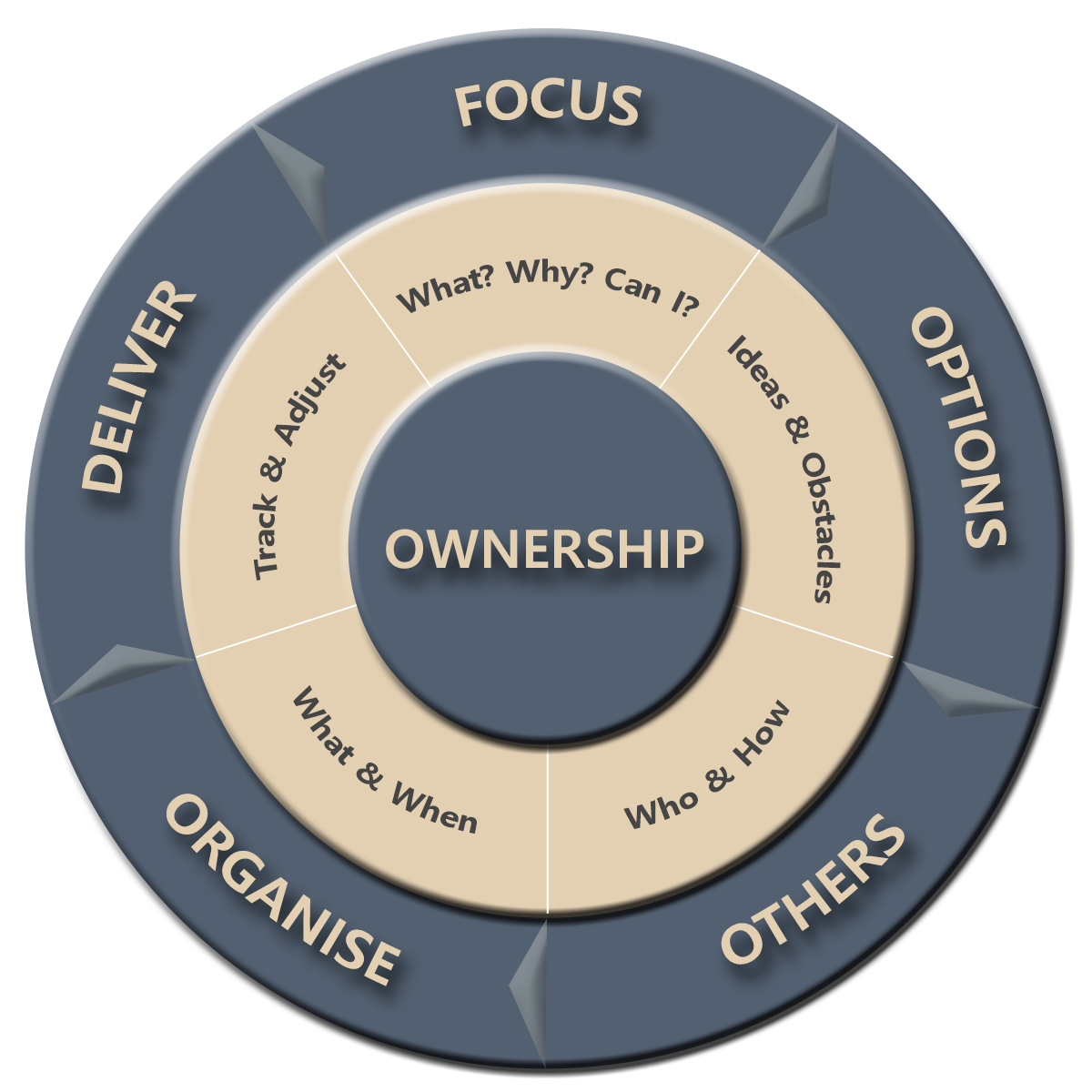

This podcast is part of a series about the role of leaders, exploring the nuts and bolts of what leaders need to do. It is based on a model (we created) to help aspiring leaders work out what it means to be a leader.

You can find the model, and details of all the areas at www.thinkingfocus.com/what-is-leadership